One challenge often heard is that the field of social and emotional learning lacks a precise definition. For example, many could point out that SEL can mean anything from lessons about what emotions are, to restorative practices, to growth mindset training.[1] Some observers have noted that the phrase “SEL'' is so broad as to possibly be meaningless. Many schools report having an SEL initiative, but what that means in practice can vary widely. This makes it hard to evaluate the claims of SEL advocates.

While this criticism has some validity, we do not think it is the main problem. The complaint that SEL lacks a clear definition masks a common feature to most social and emotional learning initiatives: a narrow framing of social-emotional phenomena in terms of skill.

We show below that no matter where you look, no matter what the program or idea is called, central to almost all discussions, programs and evaluations is a focus on the identification of skills gaps and development of skills. This may seem unproblematic. We argue, however, that this “skillsification” of social and emotional phenomena is part of the reason SEL has failed to be of great benefit. Framing SEL as a set of discrete skills to be taught or induced through social games has profound consequences.

The “skillsification” of social-emotional life

We all have long been accustomed to talk about “critical thinking” skills and “soft skills” such as communication. While Maria and I have for some time teased our friends and colleagues that the phrase “critical thinking” betrays an absence of the very thing being referenced — uncritical thinking isn’t really thinking, is it — not until we started to carefully review the social and emotional learning literature did we start to question all the skills-talk.

In reviewing news articles about SEL, we found this article in Education Week. It stands out because it is so representative of what we found in our review. According to the article, grants from the United States Department of Education (ED) were supporting efforts to embed “daily readiness assessments” in kindergarten classrooms. “Nearly one-third of the skills [teachers have] been trained to look for are in the domain of ‘social foundations,’ which includes skills such as expressing concern for others, following multi-step directions, and working cooperatively.” These skills, readers are informed, are to be ranked along a continuum of “not yet evident”, “in progress” or “proficient”.[2] This last point is key, as it defines what is meant by skill: quantified and ranked behavior.

We identified “showing concern for others” as an example of being empathic. We then asked ourselves: is empathy a skill? We then started asking all kinds of questions. For example, as educators, we know that parents often value teachers who are caring and loving toward their children, especially in the early grades. Is such caring and love a “skill”?

We decided to see if these formulations are common. To help answer this question, we sought out reviews of existing SEL programs. We found an excellent review in the Wallace Foundation funded report produced by Stephanie Jones and her colleagues at Harvard University. They compiled a descriptive review of 25 leading SEL programs. The report was over 300 pages long, and presents a suitable overview of the field, although it is focused on the primary grades.

To frame their review, the authors provided the following definition: “social and emotional learning (SEL) refers to the process through which individuals learn and apply a set of social, emotional, behavioral, and character skills required to succeed in schooling, the workplace, relationships, and citizenship.”[3]

Social-emotional experiences are understood in terms of skills. Character is defined as a skill. And with the emphasis on citizenship, one gets the idea that even democracy is a skill.

It is important to emphasize that this definition is not unique: it echoes most definitions of SEL that we have seen. The repeated emphasis on skill in SEL literature is quite striking, reflecting a consistency that is often hard to achieve in any discipline. Review of the report shows that while SEL program focus and components widely vary, the rendering of social-emotional phenomena in skills terms unifies the field.

The more we looked, the more we observed that nearly everything had become a skill. According to Jones and colleagues, the following are conceptualized in skills terms:

- Cognitive Skills: Attention control, Inhibitory control, Working memory and planning skills, Cognitive flexibility

- Emotional Skills: Emotion knowledge and expression, emotion and behavior regulation, empathy and perspective taking

- Interpersonal Cues: Understanding social cues, conflict resolution and social problem solving, prosocial skills

- Additional Skills: Character, mindset

With these formulations, we have moved from a focus on basic skills in reading and math to an understanding of the social-emotional domain in purely skills-terms. All human attributes once discussed in their own terms — thinking, empathy, creativity, even the holy grail of “grit” — are rendered as skills. Despite their efforts to address criticisms of SEL, leading researchers Shriver and Weissberg continue discussing human attributes, such as empathy and positive peer and adult relationships, as “skills.”[4]

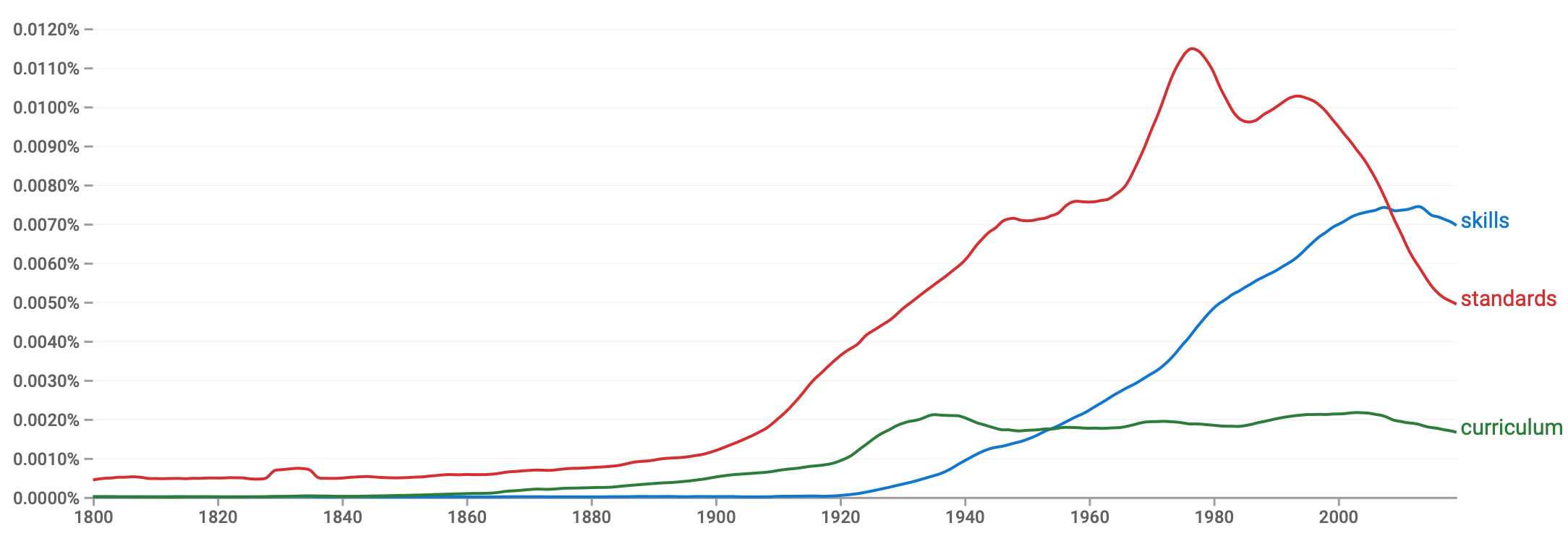

The above chart made with Google’s “Ngram Viewer” shows that the word skills occurs more frequently than the word standards; both are far more prevalent in Google’s dataset than the word curriculum. For us, this offers additional evidence that our claim that speaking narrowly in terms of skills is neither an aberration or exaggeration.

The problem with skillsification

“Skillsification” designates the process whereby dynamic social-emotional phenomena are reduced to a single behavioral output. There are, in reality, two inter-related problems here: the first is the reduction of social-emotional phenomena to a set of discrete skills, and the second is the conception of skill itself.

Let’s start with the latter first: most skills-talk in the United States is rooted in psychological behaviorism, and as we pointed out in our prior article, “instrumental reason.”[5] As the “edtech” industry makes further inroads into schools, skills-talk has been further intensified. These ostensibly “personalized” programs rely on behaviorist models of human psychology.[6] With this understanding, skill is simply the ability to perform a task to a predefined standard of competence (e.g., recall the empathy “proficiency levels” noted above).[7] Emotions and their regulation are understood as simple discrete skills abstractly no different than hitting a ball or controlling a computer mouse. Even a broader notion of skill, techne, treats human emotions as technical problems to be solved to achieve some other end.

In pointing to this, the most obvious effect of such an approach is to significantly narrow the scope and thus understanding of what it is that we are studying and acting on. If we only focus on skills, we miss out on other aspects of social-emotional life and the role these experiences play in human development. We eschew both values and purpose, and inadvertently set this robot-like skills repertoire as a desirable norm. We also accept an intensely instrumental view of humanity’s social and emotional nature. In this view, emotions should be managed to increase productivity and reduce reliance on mental health providers.

In exploring just how narrow such an approach is, let’s take just one example, empathy. It is not just really a skill, like tying one's shoes. It is an attribute of our species being. To suggest that empathy develops in a simple linear fashion (“not yet evident”, “in progress” or “proficient”), and that children can be easily ranked against each other in terms of their empathy, is at best a gross oversimplification. That a child might choose not to be empathetic but have the ability to do so seems lost on many otherwise smart researchers. People are not simple behavior emitting machines, or even simply interpreters of meaning: people evaluate the world around them and have reasons for doing what they do.

The need for an alternative conception of emotional life

While many of the basic themes identified by SEL researchers seem appropriate, their basic conceptualization is rooted in narrowly instrumental and skills-focused ideas. In the next series of articles, we explore alternative ways to conceptualize human emotion, social development, and how schools might facilitate student and staff well-being with this revised understanding.

Diane M. Hoffman, “Reflecting on Social Emotional Learning: A Critical Perspective on Trends in the United States,” Review of Educational Research 79, no. 2 (June 1, 2009): 535. ↩︎

Catherine Gewertz, “Kindergarten-Readiness Tests Gain Ground,” Education Week, October 8, 2014, http://www.edweek.org/ew/articles/2014/10/08/07kindergarten.h34.html?cmp=ENL-EU-NEWS1 emphasis added. ↩︎

Stephanie Jones et al., “Navigating Social and Emotional Learning from the inside out: Looking Inside & Across 25 Leading SEL Programs: A Practical Resource for Schools and OST Providers” (Harvard Graduate School of Education, 2017), 12, https://www.wallacefoundation.org/knowledge-center/Documents/Navigating-Social-and-Emotional-Learning-from-the-Inside-Out.pdf. ↩︎

Timothy P. Shriver and Roger P. Weissberg, “A Response to Constructive Criticism of Social and Emotional Learning,” Phi Delta Kappan 101, no. 7 (April 1, 2020): 53. ↩︎

Geoffrey Hinchliffe, “Situating Skills,” Journal of Philosophy of Education 36, no. 2 (2002): 187–205; Stephen Vassallo, Neoliberal Selfhood (Cambridge University Press, 2020). ↩︎

Mark J. Garrison, “Resurgent Behaviorism and the Rise of Neoliberal Schooling,” in Handbook of Global Education Reform, ed. Kenneth Saltman and Alex Means (Hoboken, NY: Wiley-Blackwell, 2018), 323–49. ↩︎

Hinchliffe, “Situating Skills,” 189. ↩︎